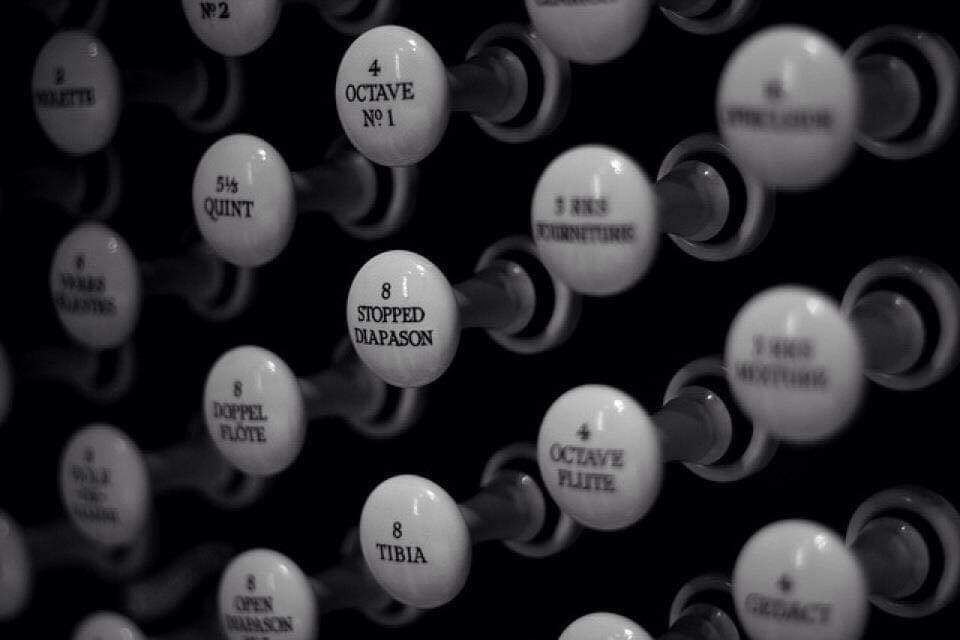

If you’ve ever seen or played a pipe organ, you’ve likely noticed rows of stop knobs or tabs, each labeled with numbers and names. These stops play a crucial role in shaping the sound of the organ, controlling which pipes will speak and how they will sound. But what do the numbers on these stops mean?

In this blog post, we’ll dive into the world of organ stops, focusing on those intriguing numbers and what they tell us about the organ’s pitch, tone, and function.

What Are Organ Stops?

Before discussing the numbers, let’s quickly review what an organ stop is. Stops are controls that allow an organist to select specific sets of pipes (called ranks) to be used when keys are pressed. Each stop corresponds to a rank of pipes that produces a particular timbre and pitch. By combining different stops, organists can create a wide variety of sounds, from a soft, flute-like tone to a loud, brassy sound.

The Significance of the Numbers

The numbers on organ stops indicate the pitch of the pipes controlled by that stop. These numbers are measured in feet and refer to the length of the longest pipe in the rank when playing the note C. The length of the pipe is directly related to the pitch: longer pipes produce lower pitches, while shorter pipes produce higher pitches.

1. 8′ Stop – Standard Pitch (Unison)

The number 8′ (eight feet) is the most common number you’ll see on organ stops. This stop represents the unison pitch, meaning the sound it produces is at the same pitch as a piano key. If you press middle C on the keyboard, an 8′ stop will play middle C, exactly as you’d expect it to sound.

For this reason, 8′ stops are considered the foundation of organ tone and are used in most combinations to form the basic sound.

2. 4′ Stop – Octave Higher

A stop marked 4′ sounds one octave higher than the key pressed. This is because the pipes in this rank are half the length of those in an 8′ rank. If you press middle C with a 4′ stop selected, the note you hear will be the C an octave above middle C.

The 4′ stop adds brightness and clarity to the organ’s sound, often used in combination with 8′ stops to enrich the tone.

3. 16′ Stop – Octave Lower

Conversely, a stop labeled 16′ produces a tone that is one octave lower than the key pressed. These pipes are twice as long as the ones in the 8′ rank. Pressing middle C with a 16′ stop selected will sound the C an octave below middle C.

The 16′ stops are typically used for adding depth and richness, especially in the pedal division, where they create a powerful, low-end foundation.

4. 2′ Stop – Two Octaves Higher

A 2′ stop plays two octaves higher than the key pressed. These pipes are much shorter—only a quarter the length of the pipes in the 8′ rank. If you press middle C, you’ll hear the C two octaves above.

While not as common as the 8′ or 4′ stops, the 2′ stop can add a sparkling, high-end brilliance when combined with other stops.

5. 32′ Stop – Two Octaves Lower

A 32′ stop sounds two octaves lower than the key pressed. These pipes are massive, sometimes over 30 feet long! Pressing middle C with a 32′ stop will produce the C two octaves below, resulting in a deep, rumbling bass.

These stops are usually found in larger organs and are typically used in the pedal division to produce very low, thunderous notes.

Mutations and Mixtures – Fractional Stops

In addition to whole-numbered stops, you might encounter stops with fractional numbers like 2 2/3′, 1 3/5′, or 5 1/3′. These are called mutation stops, and they sound at pitches that are not octaves of the played note.

For example:

A 2 2/3′ stop sounds a fifth above the key played. Pressing middle C would produce the G above the C an octave higher.

A 1 3/5′ stop sounds a third above the played note.

These stops are often used in combination with others to create unique and complex harmonic textures, adding color and richness to the organ’s sound.

Another category is the mixture stop, which contains multiple ranks of pipes that sound simultaneously at different pitches, including octaves and mutation intervals. Mixture stops are used to brighten and enhance the tonal complexity, especially in larger musical settings.

Putting It All Together: A Few Examples

Imagine playing a chord on the organ with the following stops engaged:

8′ Principal

4′ Octave

2′ Fifteenth

2 2/3′ Nazard

Pressing middle C would result in the following pitches being heard simultaneously:

C (unison pitch, from the 8′ stop)

C (one octave higher, from the 4′ stop)

C (two octaves higher, from the 2′ stop)

G (one octave and a fifth higher, from the 2 2/3′ stop)

This combination creates a full, rich sound with harmonics reinforcing each other in different registers.